The Bladensburg Races

The fledging D.C. Militia was tested during the War of 1812. Maryland and Virginia, pre-occupied with attacks on their own territory, were sluggish to send troops to D.C. The D.C. Militia, even when augmented by regular forces, was overwhelmed and ordered to withdraw. They watched the nation’s capital burn. After this incident, Congress took notice and increased the size and equipage of the D.C. Guard.

The Civil War

Maryland and Virginia were both slave states at the beginning of the war, surrounding Washington with potential enemy territory. Three days before the shots at Fort Sumter, President Lincoln called up the D.C. Militia to protect the capital, making it famous for being “the first man…first company…first regiment” called to duty for the Civil War. The decision to fight to protect the Union was not unanimous, as three companies of D.C. Guardsmen fought for the Confederacy.

Maryland and Virginia were both slave states at the beginning of the war, surrounding Washington with potential enemy territory. Three days before the shots at Fort Sumter, President Lincoln called up the D.C. Militia to protect the capital, making it famous for being “the first man…first company…first regiment” called to duty for the Civil War. The decision to fight to protect the Union was not unanimous, as three companies of D.C. Guardsmen fought for the Confederacy.

The D.C. National Guard saw an unfortunate first, when Private Manual C. Causten became the first Military Prisoner of War during the Civil War. D.C. National Guard Soldiers were on active duty for four years, fighting in the Battle of Manassas and the Valley campaign. They maintained their historical role as the Capital Guardians manning the forts which encircled Washington, D.C. At Fort Stevens, D.C. Soldiers included African-American Quartermaster clerks who were originally not allowed to join combat regiments. As D.C. faced attack from the Confederate army, they were issued rifles and told to defend their city. President Abraham Lincoln traveled to view the fighting, where he was pulled from harm’s way by a D.C. Guardsman. It would be the only time in history that a standing president would face enemy fire.

Patriotic Fervor in the Post-War Years

During the post-Civil War years, public support for the D.C. National Guard was at a new high. Encampments were held on the National Mall. Parades and marching competitions were popular spectator events. Our rifle team was nationally known. Ceremonial Marching Units, such as the Corcoran Cadet Corps, known for their snappy uniforms and precision drill, were popular forms of entertainment. John Phillip Sousa, the march king, composed two marches for D.C. Guard units.

Protecting our Nation's Borders

From its earliest days, the D.C. National Guard remained ready to accept the call to protect our nation, participating in the Creek, Seminole and Mexican Wars. In 1898, the D.C. National Guard’s 1st Volunteer Infantry fought alongside the United States Volunteers during the Spanish-American War, where they earned credit for the Santiago Campaign. The D.C. National Guard served with border patrols on the Southwest border in 1916 during the Pancho Villa raids, a mission similar to the one they would return to in the 21st century in support of Customs and Border Protection.

World War I

Fearing espionage, the D.C. National Guard was recalled to active duty seventeen days before the U.S. officially entered WWI to protect reservoirs and power plants around the city. City officials felt that they could trust the D.C. Guard for this duty, knowing that the men were from the communities they would protect. In 1917, The 1st Separate Regiment was mustered into service and renamed the 372d Infantry. The U.S. was unsure of what to do with an African-American regiment, so they were attached to the French army’s 157th “Red Hand” Division. The Soldiers fought in Meuse-Argonne, Lorraine and Alsace, where they were awarded the Croix de Guerre—one of the highest honors of the French Military. The unit was given the Red Hand name as an honor, which the 372nd Military Police Battalion still uses.

Fearing espionage, the D.C. National Guard was recalled to active duty seventeen days before the U.S. officially entered WWI to protect reservoirs and power plants around the city. City officials felt that they could trust the D.C. Guard for this duty, knowing that the men were from the communities they would protect. In 1917, The 1st Separate Regiment was mustered into service and renamed the 372d Infantry. The U.S. was unsure of what to do with an African-American regiment, so they were attached to the French army’s 157th “Red Hand” Division. The Soldiers fought in Meuse-Argonne, Lorraine and Alsace, where they were awarded the Croix de Guerre—one of the highest honors of the French Military. The unit was given the Red Hand name as an honor, which the 372nd Military Police Battalion still uses.

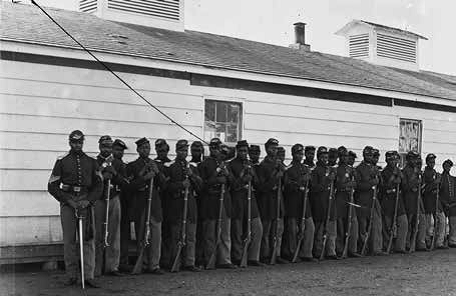

Photo: Enlisted men of the 1st Separate Battalion, an all African-American unit, examine weapons in the old DC Army arms room, September 1916, prior to entering the War in Europe.

World War II

When the U.S. entered World War II, the D.C. Guard mobilized immediately. The D.C. National Guard was home to the headquarters of the famed 29th Infantry Division. America depended heavily on the training and experience the National Guard possessed to form the backbone of a military rapidly filling with new recruits and draftees. National Guard units grouped together to train before going overseas to war. The D.C. National Guard’s 121st Combat Engineers was among the first units on the beaches of Normandy on D-Day. Other D.C.N.G. personnel fought in the Pacific theater.

In 1940, the 121st Observation Squadron was organized and began operations out of Bolling Field. At the end of the war, it was merged with the 121st Fighter Squadron, Single Engine, and the 352d Fighter Group, creating the lineage of the 113th Wing. The 113th Wing carries campaign credit from the Antisubmarine Campaign, the Po Valley Campaign, the North Apennines Campaign and the Rome-Arno Campaign.

The Cold War Era

At the end of WWII, the D.C. National Guard faced the enormous task of restructuring and retraining. The Cold War years marked a new relationship between the National Guard and active military. Fear that the United States might face an attack from the Soviets prompted high levels of readiness at home. National Guard units saw frequent deployments and activations during these years.

In 1947, the Air Force was designated as a separate branch of the military. The D.C. Air National Guard became a reality in 1950, when the 113th Wing received federal recognition.

In 1951, the D.C. Army National Guard’s 715th Truck Company became one of the few National Guard units to mobilize for the Korean War. They called their orderly room in Korea the Blair House after the President’s Guest House.

In 1961, the 113th Wing spent a year activated in support of the Berlin Crisis. In 1968, they were activated by President Lyndon Johnson in response to the Pueblo Crisis. The bulk of the unit was assigned to Myrtle Beach, South Carolina. Later, many of these Airmen deployed to the Vietnam Theater of Operations.

Vietnam

During the Vietnam War, the most notable thing about the National Guard was that it had been purposefully left out of the war. Fear that a National Guard call-up would prove unpopular kept most National Guardsmen out of the fight and would change the way that Americans viewed the Guard for years to come. As part of the individual or “levied’ replacement program, Air National Guard pilots were allowed to deploy to Vietnam. The 113th Wing established a Replacement Training Unit to send F-100C Super Sabre pilots to the conflict. In 1968, Lieutenant Colonel Sherman Flanagan, a D.C. Guardsman, was shot down in Vietnam, one of the few National Guard casualties.

The Total Force Policy

After the Vietnam War, congress mandated that all components of the military be treated as a total. The military was re-structured to make it impossible to go to war without the National Guard. During the Persian Gulf War, seven D.C. Army and Air National Guard units were deployed. The 113th Wing also served a duty rotation for Operation Southern Watch, patrolling the no-fly zone mandated over Iraq at the end of the Persian Gulf War.

Two Army National Guard units, the 715th Public Affairs Team and the 273rd Military Police Company were called up for support during Operation Joint Endeavor, the peacekeeping mission in Bosnia.

Attacks of September 11

On the morning of September 11, 2001, a duty officer from the 113th Wing, D.C. Air National Guard, called a contact at the Secret Service to see if the attacks in New York had created any airspace restrictions. Moments later, the Secret Service called with instructions from the White House to get the F-16s in the air. The Pentagon had just been hit, and the White House knew another airliner—United Flight 93—had been hijacked.

On the morning of September 11, 2001, a duty officer from the 113th Wing, D.C. Air National Guard, called a contact at the Secret Service to see if the attacks in New York had created any airspace restrictions. Moments later, the Secret Service called with instructions from the White House to get the F-16s in the air. The Pentagon had just been hit, and the White House knew another airliner—United Flight 93—had been hijacked.

After a call with the White House operations center, the 113th Wing commander issued a scramble order to set up a combat air patrol over D.C. and deter all aircraft within 20 miles with “whatever force is necessary… to keep from hitting a building downtown.”

As the first F-16 crew returned due to fuel, the next crew went out. There was no time to arm them with missiles, so each fighter went out with only 500 training bullets—just enough for a five-second burst. At the time, they believed that there may be more hostile aircraft. Each committed to doing whatever necessary to stop any hostile aircraft they encountered—up to and including ramming the airliner. By this point, fighters from Langley and the fighters from the D.C. National Guard were put in contact with each other. Flight 93 was no longer a threat, but the two units worked together to escort aircraft out of the airspace.

Meanwhile, with little more information than several people at the Pentagon were dead and several more injured, D.C. Army National Guard helicopter pilots were launched from Davison Army Airfield to the site of the attack on the Pentagon. They began ferrying casualties to Walter Reed and medical personnel back to the Pentagon.

In the days after September 11, 600 Soldiers from the D.C. Army National Guard were mobilized around the city, including the Capitol building. The Mobilization Augmentation Command reported to duty immediately, becoming the first National Guard unit mobilized for the Global War on Terror. The support was only beginning on 9/11. D.C. National Guard Soldiers and Airmen served stateside providing security at Joint Base Anacostia-Bolling, Joint Base Andrews and the Pentagon.

The Capital Guardians

The D.C. National Guard is more than a reserve force for the active duty forces—it retains a mission as protector of the District of Columbia. The Capital Guardians have held their guard posts not only during times of war but have protected Americans in times of civil unrest and natural disaster.

During the 1960s, unprecedented numbers of Americans came to Washington to demonstrate. The D.C. National Guard was activated during several Vietnam War and Civil Rights demonstrations.

When Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated in 1968, riots broke out across the country. Over 1,800 D.C. National Guardsmen were called up to protect the city. Many of the Guardsmen left their own homes and families at risk.

The D.C. National Guard maintains the tradition of serving D.C., providing security for city and national events. The D.C. National Guard has proved to be a responsive, dependable force for more recent missions such as Independence Day celebrations on the National Mall, the Million Man March, the Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial dedication and state funerals. Capital Guardians have served in times of natural disaster, deploying in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, the blizzard of ’96, the “Snowpocalypse” blizzard of 2010, Hurricane Irene, Hurricane Sandy and many other natural disasters.

Global War on Terror

The D.C. National Guard has deployed more than 1,200 Soldiers and Airmen to support the Global War on Terror. The D.C.N.G. completed over 90 whole-unit deployments, including tours in Iraq, Afghanistan, Guantanamo Bay, Saudi Arabia and stateside missions as part of Noble Eagle. Many D.C. National Guard Soldiers and Airmen served multiple deployments.

Since September 11, 2001, the 113th Wing has provided twenty-four-hour protective coverage over the skies of our Nation’s Capital.